Blog | 18 Feb 2021

The challenges of forecasting during a pandemic

Innes McFee

CEO

The global pandemic has been a huge test for economic forecasters. An event unprecedented in modern times has precipitated a contraction in the global economy far greater than in 2008-2009, and it unfolded over the course of weeks rather than quarters.

So what makes a good economic forecast in such times? What makes a forecast as useful as possible for clients trying to make business decisions and formulate strategies?

We believe forecasts must display agility, balance, and a quantification of risks:

- Agility – Forecasts must move quickly to incorporate the very latest information and make appropriate inferences about the future.

- Balance – They must not overreact to events and oscillate wildly. Our clients cannot plan if we aren’t giving them a consistent view on the economy from one day to the next.

- Quantification of risks – We acknowledge that many plausible scenarios exist, and the baseline is just the one to which we attach the highest probability. Scenarios can allow clients to pivot quickly to alternative economic assumptions if the outlook changes quickly.

It’s a fine balancing act; we must move quickly but also proportionately. We must present a strong case for the baseline but also warn about risks.

Keen to ensure that we live up to these aims, we constantly measure ourselves against other forecasters and against our own standards. Normally, we would do so with reference to our forecast awards or our analysis of observed forecast errors.

However, the global pandemic was, to all intents and purposes, a completely unpredictable event. As such, the usual exercise of comparing January forecasts with calendar year outcomes aren’t very informative. Between January and April 2020, we cut our forecast for global GDP growth from 2.6% to -3.5% – by far the largest three-month downward revision in the company’s 40-year history.

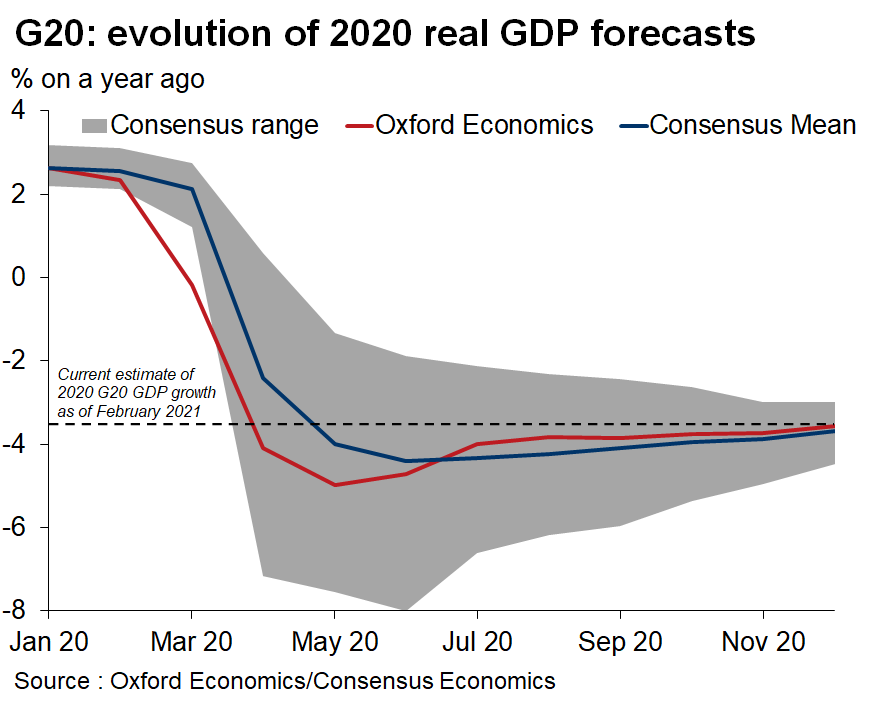

Instead, to assess the quality of our forecast, we look at how it has evolved over the year relative to other forecasters for the G20 economies. While our forecasts cover 200 economies, the G20 accounts for 80% of global GDP, and its nations are markets that offer a good pool of competitors against which we can benchmark our response.

The chart shows how our forecasts for GDP growth (red line) in the G20 economies, weighted together, evolved over the course of the year compared with those published in the monthly Consensus Economics publication (blue line and grey swathe). We actually update our forecasts for the large economies twice a month to provide a timelier view for clients, but here we present just our first forecast release each month for ease of comparison.

The chart shows how our forecasts for GDP growth (red line) in the G20 economies, weighted together, evolved over the course of the year compared with those published in the monthly Consensus Economics publication (blue line and grey swathe). We actually update our forecasts for the large economies twice a month to provide a timelier view for clients, but here we present just our first forecast release each month for ease of comparison.

The overall picture is clear. In early 2020, we moved to downgrade our forecast more quickly than other economists, at times leaving us outside the consensus range altogether. But by midyear we were already upgrading our forecast as it looked like distancing measures would be relaxed. From then on the forecast trended toward what we currently estimate to be the G20’s final 2020 GDP growth number: -3.5%.

Three key points in time are worth focussing on:

- March 6, 2020 – We cut our forecast from 2.3% to -0.2% as it became clear that what we had initially thought was a supply shock from China was morphing into a full-blown global crisis. This placed us a full percentage point below the even most pessimistic forecasters in the market.

- July 8, 2020 – Having reached our most pessimistic point two months prior, we made a significant upgrade to the global outlook, reflecting signs that consumers were set to release some pent-up demand from the first lockdown and that policymakers were acting decisively. This made us more optimistic than the consensus for the first time in 2020.

- December 8, 2020 – In the second half of the year, our 2020 forecast barely changed, moving only slowly to what we now, in February 2021, believe is the outturn for the year. Even at the end of the year, with the benefit of a more complete dataset, other forecasts still showed a large amount of uncertainty about the final GDP growth number for 2020.

Throughout early 2020, we regularly updated three key global scenarios to quantify the risks around the baseline. Early iterations of our global downside scenario turned out to be too optimistic, but at least they gave clients a sense of the direction of travel and the magnitude of risks the global economy faced.

We can certainly do some things better, but overall we hope clients found our forecasts to be agile and balanced, and that our scenarios quantified the risks accurately.

Tags: