Blog | 24 Apr 2024

The latest export from China is … deflation

Tatiana Orlova

Lead Economist, Emerging Markets

In recent months, the Chinese economy has experienced deflationary pressures, a trend that seems poised to persist. As a result, emerging markets (EMs) are likely to see sustained disinflation in non-oil import prices, a development that could have diverse implications across different regions.

China’s export price drop: a closer look

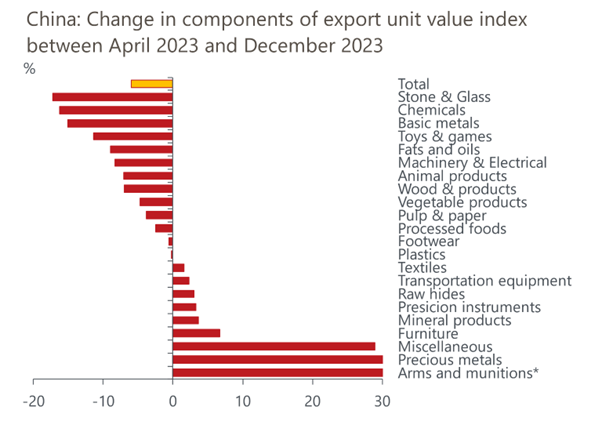

From April to December 2023, Chinese export prices fell by 6%. Among the categories comprising the total export unit value index, stone and glass export prices decreased most, followed by chemicals and basic metals. But the relatively large contribution of machinery and electrical equipment (estimated at 30.7%) ensured that this category contributed most (almost 3ppts) to the 6% decrease in the total index during that period. This is a very broad category that includes inputs into sectors like renewables and solar energy – key sectors that the US and other advanced economies are particularly keen to develop.

Prices of machinery and electrical equipment exports fell 8.4%

*Changes in Arms and Munitions and Precious Metals components are off the scale

The second-largest contribution came from basic metals. This suggests that China’s overproduction of steel and aluminium in the wake of the bursting of its housing market bubble is now spilling over to global markets, depressing prices for these metals.

China’s car exports, particularly its EV exports, have soared recently. In 2023, China exported 5.22mn cars, second after Japan (5.97mn). Cars, including electric cars, fall under the category of transportation equipment, which has a relatively low weight (2.2%) in the total export unit value index. But in the context of China’s rapidly growing car exports, the global significance of Chinese car export prices is rising. Cars are included in the subcategory of rail locomotives, cars, track and signal. In annual terms, export prices in this subcategory have been in an annual decline since mid-2022.

We believe the recent collapse in China’s export prices is triggered by the particular nature of its domestic stimulus. The policy of pouring fiscal resources into investment and expansion of production facilities intensifies overcapacity risks. When external demand is insufficiently strong to absorb excess production, export prices fall, becoming a channel through which China exports its deflation to the rest of the world.

China’s deflation has caused a sharp decline in emerging market import prices

Despite the derisking and onshoring policies promoted by advanced economies in recent years, China still plays a predominant role in global manufacturing chains. When China’s export prices drop, its exports become more competitive, affecting local industries in the countries importing Chinese goods.

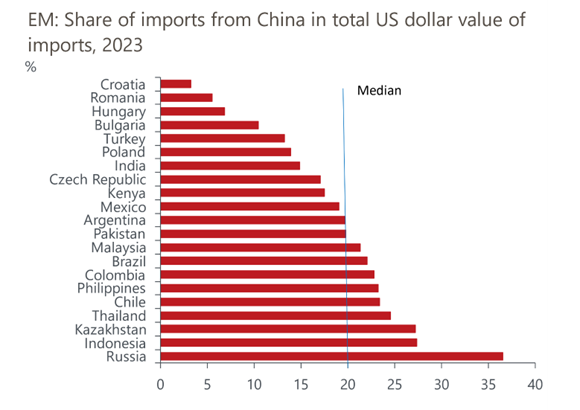

Emerging market import prices are highly correlated with China’s export prices. The median share of China’s imports in the total value of emerging market imports in our emerging market sample is quite considerable at 20%. Our EM Import Prices Index constructed from the data available for nine emerging market economies began to fall in April 2023.

As many emerging markets also import components, spare parts and machinery and equipment used in local production processes from China, the other channel of transmission of cheaper Chinese imports into lower local inflation is via the prices of these categories of goods. The results of this transmission are likely to show up in emerging market producer prices. That said, they may be partially obscured by secondary effects from China’s industry-oriented stimulus, for example, by increases in prices of commodities used by emerging market producers, as higher Chinese demand for these commodities fuels global demand.

Meanwhile, China’s reinvigorated support for manufacturing increases overcapacity risk in state-favoured industries such as renewables and batteries, exacerbating disinflationary pressures. In combination with other factors supporting emerging market disinflation, China’s generally deflationary environment will contribute to a decline in annual average inflation in emerging markets, which we anticipate will fall to 5.6% this year on average in our sample.

Impact of Chinese deflation will differ across emerging market economies

We expect to see significant disparities in the extent to which Chinese deflation is transmitted into local consumer prices across emerging markets. One reason is the structural differences among different economies such as market structure, competitiveness, and relative costs, which inform firms’ response to changes in input prices. Another reason is that the share of China’s imports in total imports differs significantly across emerging markets. In our sample of 21 emerging market economies, it ranges between 3% in Croatia and 37% in Russia.

Russia has the highest share of Chinese imports in total imports (37%), and stands out as a likely beneficiary of the disinflationary influences stemming from lower Chinese import prices. Indonesia (27%) and Kazakhstan (27%), also stand a good chance of bringing their inflation closer to targets this year due to imported deflation.

The impact will be lower for other emerging markets whose trade links with China are weaker – most notably, those in Europe (Croatia, Romania, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland), but also Turkey. Even for these economies, however, Chinese disinflation may remain a potent force given the indirect impact on competitors’ prices.

In advanced economies, the US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has recently blamed soaring Chinese imports for hollowing out industry in parts of the US, and hinted at the possibility of new tariffs. Earlier, she expressed concern that China’s industrial policy was creating substantial overinvestment that “hurts American firms and workers, as well as firms and workers around the world”. However, there are no signs that China intends to alter its policies in response to the threat of additional tariffs.

Author

Tatiana Orlova

Lead Economist, Emerging Markets

+44 (0) 20 3910 8048

Tatiana Orlova

Lead Economist, Emerging Markets

London, United Kingdom

Tatiana joined OE in May 2021. From 2017 to 2021, she ran her own macroeconomic research boutique, Emerginomics, as the Founder and Chief Economist, specializing in coverage of selected ex-USSR economies.

From 2012 to 2016, she worked as Director in CEEMEA Research at the Royal Bank of Scotland. Previously, she was employed as an emerging market economist in three other major investment banks (Credit Suisse, ING, and Nomura).

Tatiana holds an MSc in Economics from the LSE (2001) and Diploma in Economics with Distinction from the LSE (2000). From 1988 to 1994, she studied Applied Mathematics at the Moscow University of Electronics and Mathematics.

Tags:

Related Reports

Steady, Yet Slow: How Oxford Economics Sees Global Economic Growth in 2025

Czech Republic: Near-term recovery, long-term struggle

Emerging Markets Key Themes 2025: Baseline looks fine but tariff risks severe

China Economy

Read more analysis on real estate performance and location decision-making.

Read more: China Economy