Ungated Post | 01 Feb 2021

Australia, the lucky country once again?

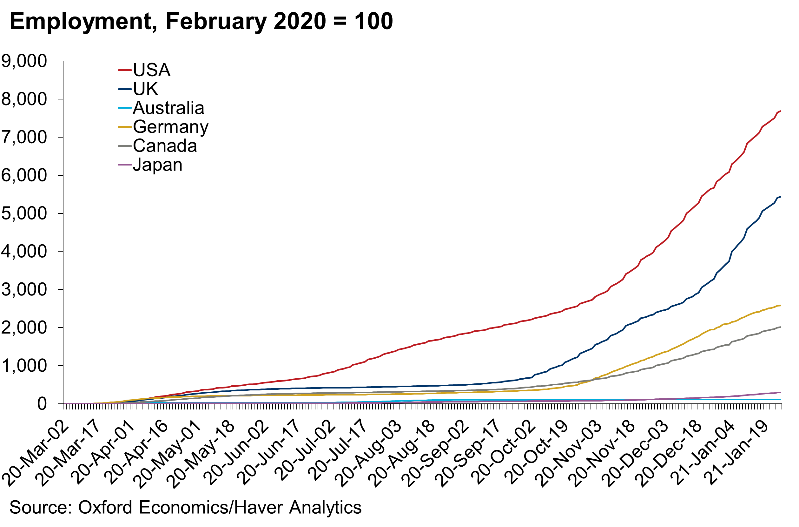

Australia’s experience with the COVID-19 pandemic fits the country’s moniker as the Lucky Country. The number of cases has been exceptionally low compared with other developed economies, the contraction in output smaller, and the recovery more robust.

Dumb luck has played a part in this. Isolation from the rest of the world made it relatively easy to close the country’s borders, as cross-border flows of people are naturally much lower than in Europe and North America. The concentration of the population in a small number of cities, and relatively low urban density also helped the authorities initially contain the spread and then prevent subsequent outbreaks from moving around the country.

Dumb luck has played a part in this. Isolation from the rest of the world made it relatively easy to close the country’s borders, as cross-border flows of people are naturally much lower than in Europe and North America. The concentration of the population in a small number of cities, and relatively low urban density also helped the authorities initially contain the spread and then prevent subsequent outbreaks from moving around the country.

But the country has also made its own luck. The authorities responded early, arguably before the full extent of the crisis was clear. They acted quickly to close the international border in early-February, with all international arrivals required to complete quarantine from late-March onwards. And public health officials began to build test, track and trace capacity and medical stockpiles from late January onwards, resulting in no major shortages through the early months of the pandemic.

For the economy, the Federal government and central bank moved quickly and decisively. The RBA was one of the first central banks to put emergency levers in place, and by the end of March the Federal government had committed over A$150bn in direct support (around 8% of GDP), one of the largest packages amongst the G20.

So will the country’s luck last? Somewhat ironically one of the central pillars of the country’s COVID response—the closure of the international border—is having a permanent, negative impact on the economy. In normal times the country attracts a substantial number of overseas migrants (239,000 in 2019), with these flows accounting for over half of all population growth.

So will the country’s luck last? Somewhat ironically one of the central pillars of the country’s COVID response—the closure of the international border—is having a permanent, negative impact on the economy. In normal times the country attracts a substantial number of overseas migrants (239,000 in 2019), with these flows accounting for over half of all population growth.

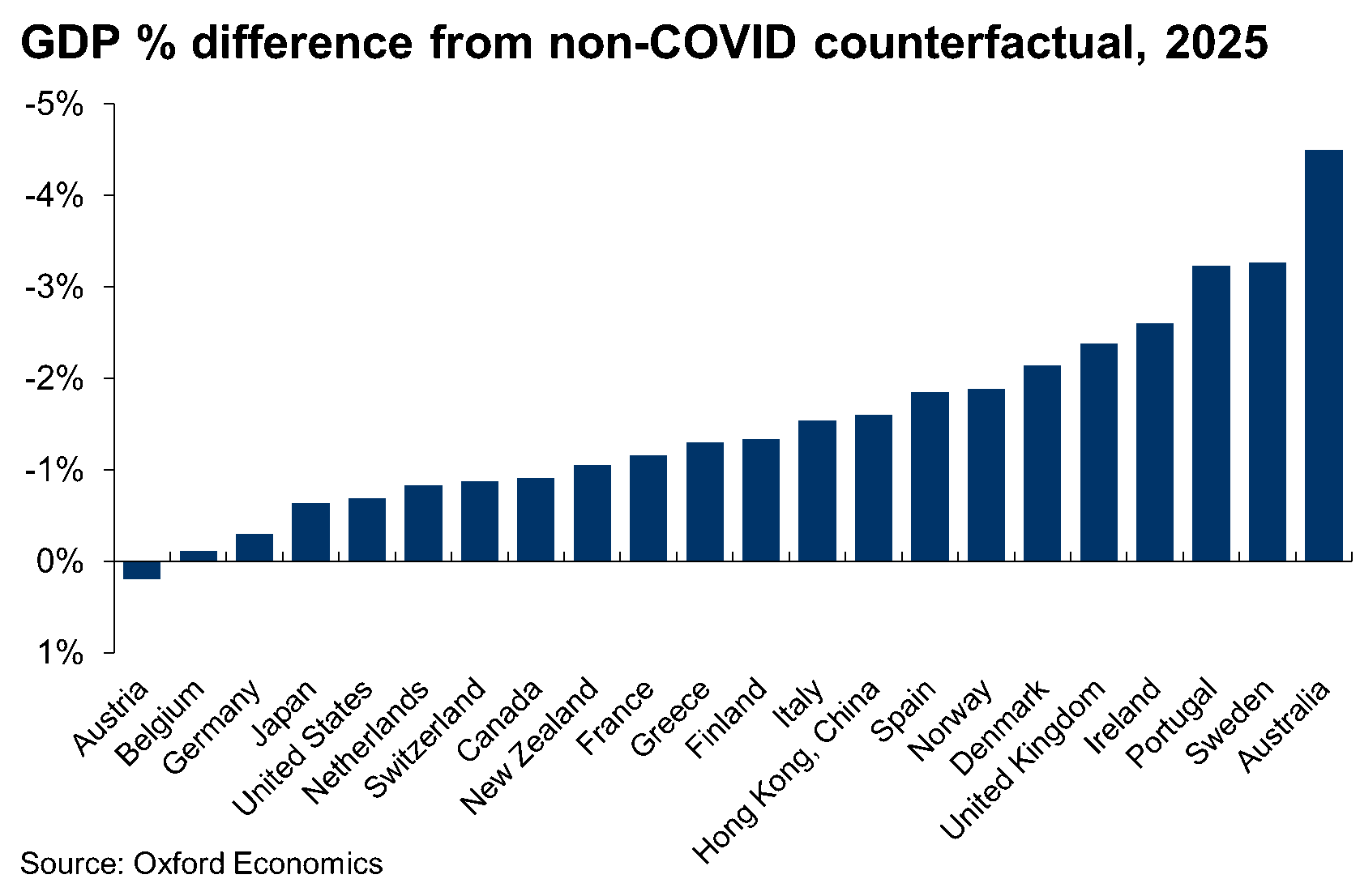

The closure of the border and return home of temporary workers and students has seen these flows turn negative, and while a recovery is expected it will take time; the government expects 1 million fewer migrants over the next four years. The resulting fall in the number of workers will reduce the economy’s productive potential by around 4%. As a result, the long-run economic impact of COVID will likely be the largest amongst the developed economies.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Oxford Economics announces a leadership transition for the next phase of growth

Oxford Economics, the world’s leading economic forecasting and advisory firm, announced today the appointment of Innes McFee as its new Chief Executive Officer, effective 4th December.

Find Out More

Post

Oxford Economics launches enhanced Real Estate Economics Service

Oxford Economics is pleased to unveil its enhanced Real Estate Economics Service, now covering 100 global cities.

Find Out More

Post

Oxford Economics Acquires Majority Stake in Alpine Macro

We're excited to share that Oxford Economics has acquired a majority stake in Alpine Macro, a prominent global investment research firm based in Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Find Out More