Blog | 03 Jul 2024

Labour’s plan to build more homes is encouraging, but do not expect it to profoundly reform the market

Hugo Bessis

Senior Economist, Cities and Regions

In a previous research briefing, we looked at the macroeconomic implications of a new Labour government. Here, we delve into one of the UK’s most persistent political issues—housing—and explore what changes a Labour government might bring to regional development.

The Labour manifesto is clear in its ambition to build more homes, with a target of 1.5 million new houses over the next parliament. To do so it proposes to update and relax the National Policy Planning Framework while restoring mandatory housing targets. It also prioritises the release of disused land, whether that is brownfield (land that has already been developed) or “greyfield” (land that would qualify as brownfield but is currently within a green belt). Finally, the Labour Party proposes to deliver more houses through a set of new towns.

Essentially, Labour’s pledge is not significantly different to what the opposition has tried to achieve in the past. As we’ve explained previously, in their 2019 manifesto the Conservatives made a commitment to build 300,000 homes a year (which equates to 1.5 million over 5 years, the same as Labour), as well as to revamp the planning system. They also published a 2017 White Paper that vowed to develop new garden towns and villages. But none of this has fully materialised. Home building figures are short of their set targets, the planning system has not changed radically, and garden towns are not yet off the ground.

Housing reform is indeed complex because although it is regarded as a national challenge, the issue is very much a local one. For politicians, this means that change is often met with a lot of resistance. For policymakers, the implication is that a one-size-fits-all is rarely effective. A perfect system must be flexible enough for the market to address demand, while also protecting land, assets, and the urban fabric, and take consideration of local interests.

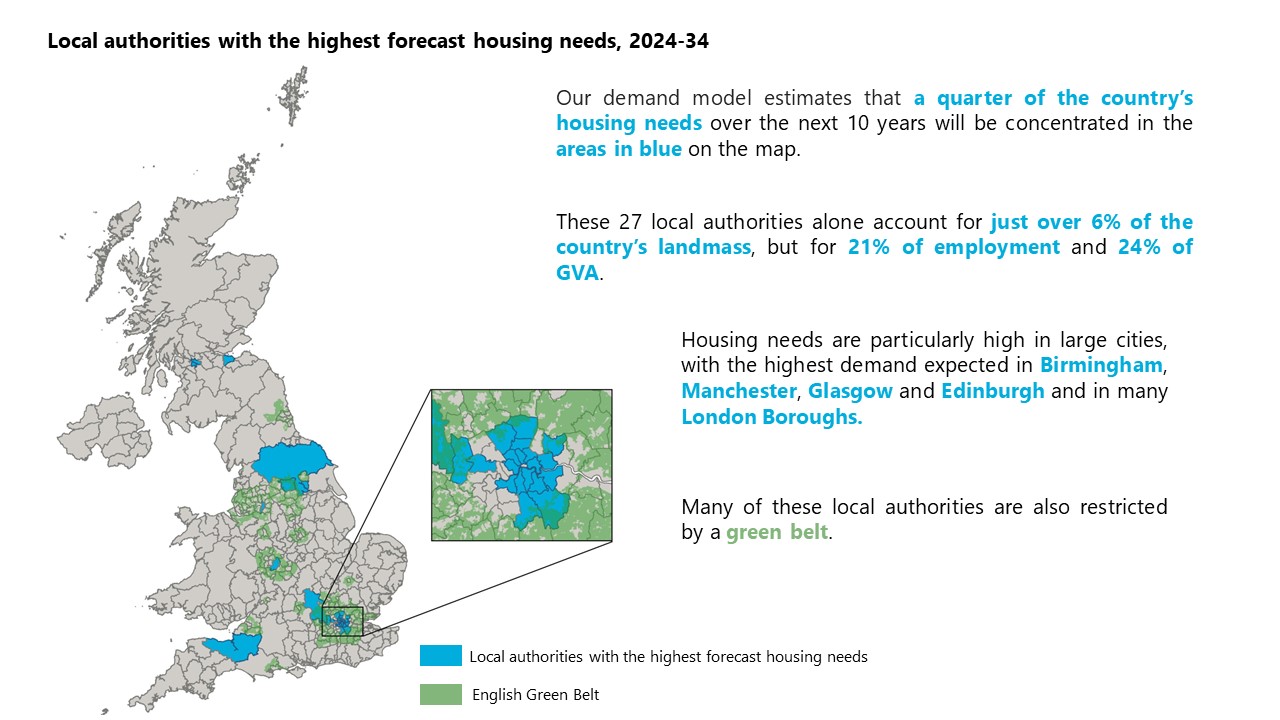

In fact, the housing crisis is mainly confined to the most prosperous parts of the country, with London and areas of South East England experiencing the most acute issues. This is where housing affordability tends to be the worst, and therefore where more homes are needed. And this is also where we expect employment and population to grow the most, further exacerbating the housing issue. We forecast that a limited group of 27 local authorities across the UK will represent a quarter of the country’s housing needs over the next 10 years, 19 of which are in London.

More housing is needed in prosperous regions to align with economic and employment growth. This will facilitate the migration of workers to more productive parts of the country, which might be positive to the national economy, but is unlikely to reduce regional inequalities. Meanwhile, as the economy continues to concentrate in these prosperous areas, there will be increasing competition for land between residential, commercial, and industrial uses. Rising land costs and growing pressure on space, coupled with the facilitated conversion of industrial and commercial space into residential, could end up threatening the supply of employment space, particularly on the high street.

Another challenge for the new government will be to find the right way to assess housing needs in a region, particularly if these targets are to become mandatory. The calculation is currently based on projected household growth in an area, with specific adjustments based on other local criteria, such as local market affordability. However, the current formula is criticised by planning and developer associations for using household population projections that date back from 2014, which disproportionately focus on housing delivery in already populated areas, and fail to reflect more recent changes in population trends. And while updated ONS projections predict lower levels of growth, we believe that these forecasts are still too high. Indeed, the ONS assumption is based on an average of net international migration inflows over the past 10 years, which was inflated by several factors that are unlikely to be repeated (such as visa schemes for migrants from Ukraine and Hong Kong, post-Covid-19 recovery in student inflows). Along with those arithmetic considerations, there is a genuine question of whether planning authorities—specifically urban ones—have the capacity to meet the proposed targets, as constraints (such as green belt land) limit opportunities. The Labour Party proposes cross-boundary housing strategies for Combined and Mayoral Authorities, which could help alleviate this issue.

Meanwhile, although re-purposing brownfield land will help meet these targets, research from Lichfields has shown that even if all brownfield sites were utilised for housing, they would only address about a third of the housing needs for the next 15 years. In reality, remediation costs, delivery times, and sites’ specific characteristics mean that many are actually not viable for redevelopment.

Ultimately, the government that emerges from the election will have limited leeway to change how housing is delivered in the UK. The track record of previous governments suggests that building enough—not just more—new homes is a nearly impossible challenge due to a variety of economic, planning, and social barriers. Yet those barriers have been clearly identified, and the acceleration in house building observed in the last decade suggests that if the new government is committed to address the issue, higher housing delivery can be expected in the future.

Author

Hugo Bessis

Senior Economist, Cities and Regions

Hugo Bessis

Senior Economist, Cities and Regions

London

Hugo is a Senior Economist in the Cities and Regions team, specialising in regional and urban economic development, socio-economic analysis, and policy.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Could the election spark renewed interest in UK-focused stocks?

The UK election has concluded with Labour securing a landslide victory. This result is likely to set the stage for a period of political stability and, combined with signs of a consumer-driven economic recovery, makes domestic-focused UK stocks increasingly attractive.

Find Out More

Post

UK General Election: Why Labour and Tory manifestos are a missed opportunity

Join Andrew Goodwin, Chief UK Economist, as he outlines the potential economic impact on fiscal policy of the manifestos published recently by the Conservative and Labour parties.

Find Out More

Post

UK Elections | Beyond the Headlines

In this week’s Beyond the Headlines, join Andrew Goodwin, Chief UK Economist, as he outlines how we’ve changed our UK interest rate forecast after a busy week for the UK economy.

Find Out More