Blog | 15 Dec 2023

Tokyo – Hotspots and some optimism in a slow-growing city

Patrick Deshpande

Lead Economist

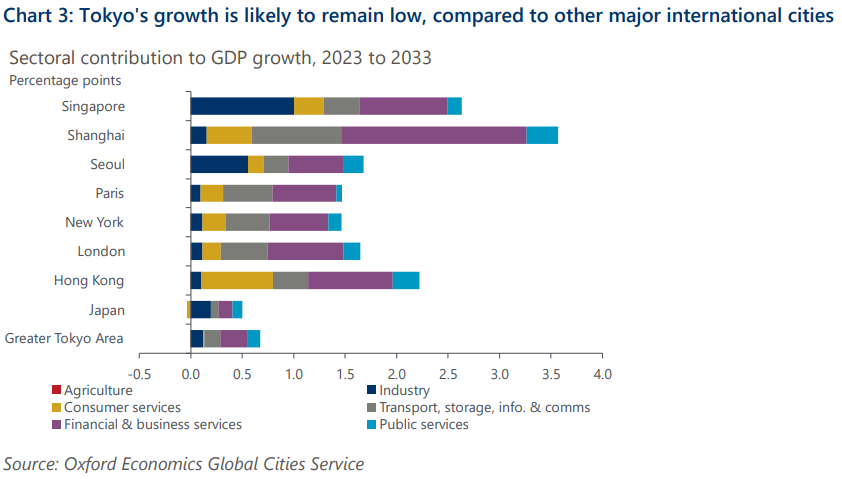

Tokyo has historically underperformed its counterparts elsewhere in Asia-Pacific and globally, having failed to develop a strong export base in high-value services to match its domestic dominance. But there are some hotspots, and structural changes in Japan create reasons for optimism. Tokyo prefecture will remain the region’s largest city in GDP terms until about 2034, when it is likely to be overtaken by Shanghai, while Greater Tokyo will dominate globally for much longer.

Demographics have clearly been a challenge, and will become more so before the end the decade

Reliance on rising employment to deliver rising GDP growth is, however, a difficult proposition in a country famous for its challenging demographics. Japan’s ageing population is well documented and compounded by low rates of international migration. While Tokyo has previously absorbed internal migration flows from elsewhere in Japan, this has not been sufficient to overcome the underlying ageing of the city’s population. We expect a tipping point in 2027, after which the population of the Greater Tokyo Area will begin to contract, with an equivalent point expected to be reached within Tokyo Prefecture in 2040. In both instances, falling population will coincide with the onset of a decline in employment.

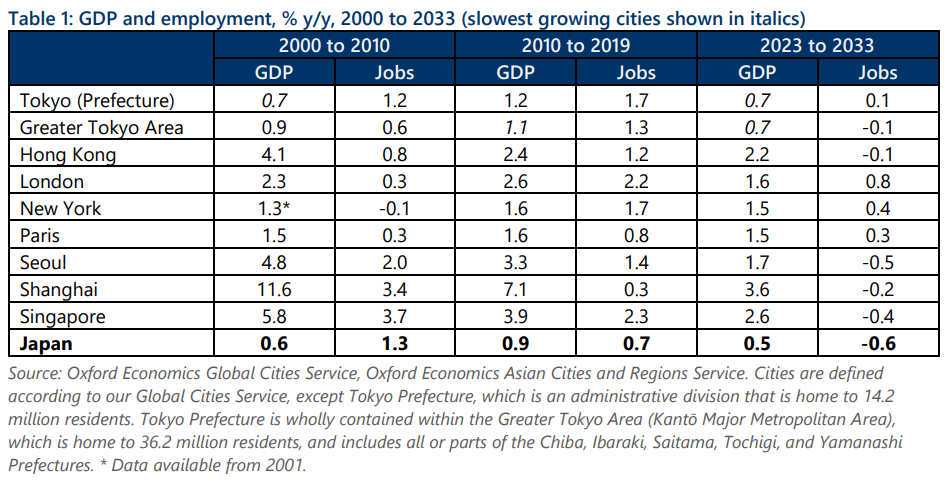

A possible source of supply would be to encourage an expansion of female labour market participation. We have previously documented the partial success that Japan has had nationally in increasing female participation in the workforce to mitigate the negative impact of its demographic challenges on growth. But the scope for expanding female participation in Tokyo may be limited. Census data indicate that Tokyo has the lowest female employment rate of all 47 prefectures in Japan, and we think this will be hard to alter. High childcare costs make full-time participation in the labour market difficult for many Tokyo mothers. But equally, high housing costs and small dwelling sizes in Tokyo mean that it is difficult for families to live in the sort of multi-generational households that elsewhere can potentially provide informal childcare. These are not challenges that are likely to be easily overcome, particularly in the short term.

Looking ahead, labour market reforms, including reducing difficulties the workers experience in moving between industries, and encouraging a transition away from seniority-based wage structures, may have some positive effects on Tokyo’s labour market. Reforms to simplify visa requirements to attract more foreign workers to the city may be particularly successful in attracting lower-skilled workers. But for highly skilled workers, they are unlikely to have much impact, unless they are associated with expectations of rising income levels and future job opportunities. Furthermore, commentators have noted Japan’s reputation for having a work-first mindset, long working hours, and formal workplace etiquette, which may dissuade foreign workers and encourage outward migration, as workers increasingly expect flexible working and an improved work-life balance.

But other factors have also prevented Tokyo from achieving its full potential

But it is a mistake to think that demographics are the only factor that have held Tokyo back, and might do in the future. Several other reasons can be identified.

First, Japanese firms have lost their comparative dominance in the high value-added technology sector. This is partly a reflection of firms becoming less price-competitive in an increasingly globalised world.

Second, Tokyo has failed to attract foreign direct investment (FDI). Alongside the direct economic activity stimulated by attracting investment in the short term, foreign investment can generate dynamic improvements in a city’s fortunes, bringing new ideas and approaches to business practices that can enable wider spillover benefits. However, Japan ranks 36th among the 39 OECD countries by inward FDI as a share of GDP, and as demonstrated in Chart below, it underperforms nearby APAC economies.

Third, alongside a failure to attract foreign capital, Tokyo suffers from low international migration. It does not enjoy the same access to the world’s most skilled labour that other more cosmopolitan global cities do. Beyond the direct impact on economic output, low international migration among highly skilled workers may have led Tokyo to miss out on less tangible economic benefits, including the injection of new cultural and business ideas that a more diverse workforce might have brought.

Fourth, and partly reflecting that point, Tokyo’s underperformance compared to other major cities is partly

due to its failure to translate its large financial and business services sector into service exports.

Particularly troubling is that in financial services, Tokyo has fallen behind its other regional competitors: according to the Global Financial Centres Index, a comparative measure of the competitiveness of leading financial centres, Tokyo’s ranking has slipped from a high fifth in 2016 to 20th in the most recent iteration, behind regional competitors such as Beijing, Shenzhen, Seoul, and Shanghai.

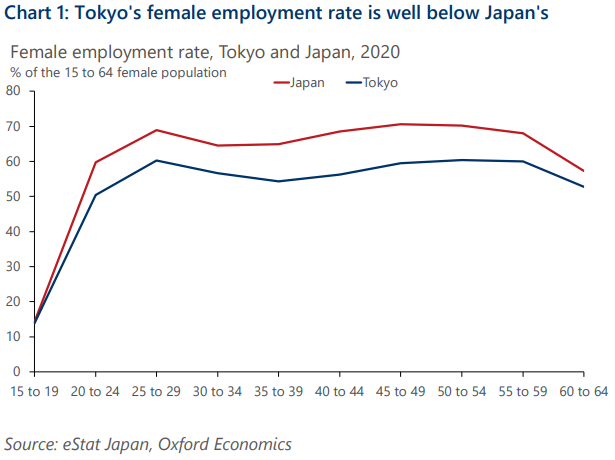

Tokyo is most likely to continue to grow at only a moderate pace

As a result of these factors, our Global Cities Service suggests that Tokyo will continue to underperform its regional and global counterparts. We forecast that over the coming decade to 2033, GDP will grow by an average of 0.7% per year in Tokyo, equivalent to under half of the rates expected across London, New York, and Paris, and a percentage point lower than the rate for Seoul.

However, the Greater Tokyo Area will continue to outperform the Japanese economy as a whole. And while other larger cities such as Fukuoka (1.1% per year) and Nagoya (0.8% per year) are due to outperform Tokyo, due mostly to thriving information & communication and industrial sectors respectively, the sheer size of the Greater Tokyo Area means that it will see a greater increase to its GDP in absolute terms than all other 24 Japanese cities in our Global Cities Service combined.

Indeed, in the long run, Tokyo will continue to be among the largest urban economies in the world. While Tokyo Prefecture is expected to be overtaken by Shanghai in GDP terms in 2034, the Greater Tokyo Area will remain the largest urban economy across the globe until at least 2050, with the third-largest workforce behind only Jakarta and Manila.

But the possibility of improved performance should not be discounted

And it is not impossible that the outlook could be rather stronger than our central or baseline projection. At the national level, Prime Minister Kishida’s “New Capitalism” reforms reflect a continuation of the “Abenomics” of the 2010s. If anywhere in Japan is particularly likely to benefit from them, then that place is Tokyo. The reforms seek to tackle many of the issues we have identified as having held back Tokyo’s economic performance, including setting ambitious targets for boosting FDI. Stock market reforms should also encourage better business practices, while improved corporate governance standards may help to make Japanese firms more agile in responding to change. The labour market is becoming more flexible and, as we discussed in a recent Research Briefing, Japan’s firms are switching from a seniority-based wage system to a performance-based one. Companies are also adopting more aggressive pricing policies, and are investing in labour-saving technology. Both should be good for economic growth.

Japan’s economic reforms also include promoting Tokyo as a centre for innovative start-ups. And at a municipal level, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government has signalled an intent to become “the most start-up-friendly” city in the world, backed up by a ¥10 trillion investment by central government. In its Global Startup Ecosystem report, Startup Genome ranks Tokyo 15th globally for its startup ecosystem, below Beijing (7th), Singapore (8th), Shanghai (9th), and Seoul (12th), but not completely out of contention. The proactive role that government is taking is a positive sign, and an emulation of the success of other APAC cities, such as Singapore and Taipei.

And Tokyo already has a dynamic business core on which it can build

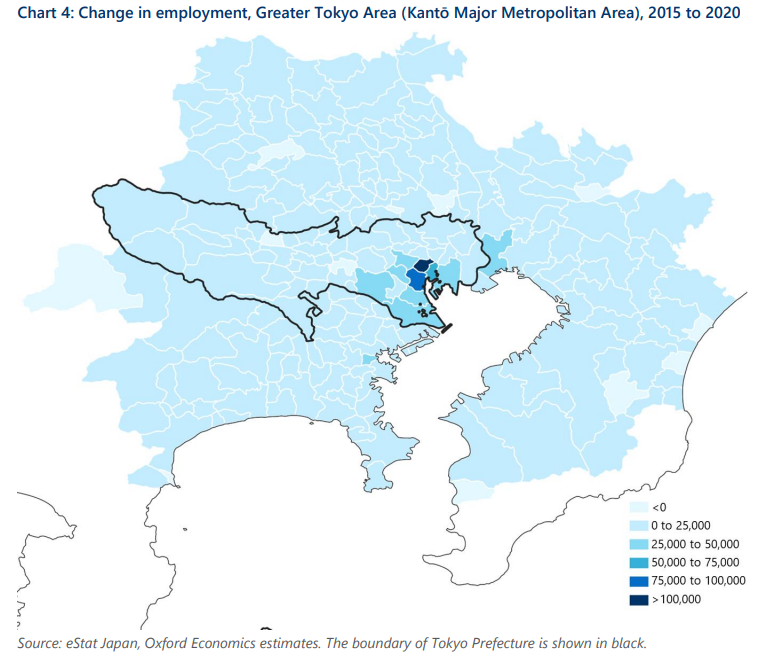

Furthermore, some parts of Tokyo are already very dynamic. An analysis of the 227 municipalities that form the Greater Tokyo Area demonstrates an increasing concentration of employment growth within central Tokyo. A comparison of employment through 2015 to 2020 indicates that while most municipalities across the Greater Tokyo Area saw an increase in employment, the changes in absolute terms tended to be modest.

Instead, employment creation has been highly concentrated within four contiguous wards in the heart of the city: Chiyoda, Chuo, Minato, and Shinagawa. We estimate that collectively these four wards contributed half of all job creation across Greater Tokyo, with growth almost entirely driven by job creation in financial and business service sectors, in particular the information & communications sector.

The dynamism of this tight-knit city core exists in the context of a range of wider city assets, from a highly efficient public transport network to world-leading retailing, restaurant and nightlife offers, very strong global connectivity, highly impressive cultural facilities, excellent healthcare, low levels of crime, and much lower levels of air pollution than many of Tokyo’s rivals. It is correspondingly possible to take a much rosier view of the prospects for the most economically successful parts of Tokyo, than the story conveyed by our headline numbers. This is of course true to some degree of all cities: but perhaps it is in the nature of Tokyo that its best assets are more hidden away than the corresponding hotspots in other cities, globally.

To learn more about how our City Services could support you, please click below.

Author

Patrick Deshpande

Lead Economist

+44 203 910 8109

Patrick Deshpande

Lead Economist

London, United Kingdom

Patrick is a Lead Economist in the Cities and Regions team, specialising in economic impact model development, socio-economic profiling, and bespoke modelling on consultancy projects. Patrick is a UK Office for National Statistics Accredited Researcher. Prior to joining Oxford Economics, Patrick was a Senior Economist in the Economic Development team at AECOM.

Patrick has a BA in Economics from the University of Leicester and an MSc in Economics from Trinity College Dublin.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Which regions are most exposed to the 25% automotive tariffs?

While the automotive tariffs will likely lead to some production being reshored to US plants, they will also raise costs for US manufacturers and households.

Find Out More

Post

Parsing US federal job cuts by metro

Cuts to the Federal government workforce, which we estimate to be 200,000 in 2025, will have a modest impact nationally, but more significant implications for the Washington, DC metropolitan economy as it accounts for 17% of all non-military federal jobs in the US.

Find Out More

Post

The European housing market has turned a corner, but challenges remain

The housing market across most of Europe has now improved, but has it reached the tipping point?

Find Out More