Blog | 15 Oct 2021

Why a US-China decoupling is not happening anytime soon

If you were to scan recent headlines, from submarine sales in the Pacific, to Chinese clampdowns on Evergrande and the Internet, to friction over the World Bank, you might think the US and China were poised on the verge of serious conflict—or even war.

There’s only one problem with this view of emerging conflict with China: it contradicts many of the economic facts on the ground.

The view that China is now the chief competitor of the United States is a given in both parties. While Presidents Trump and Biden agree on few issues, the Biden administration has kept in place Trump-era tariffs and export controls and is reportedly looking into launching an investigation into China’s large-scale industrial subsidies.

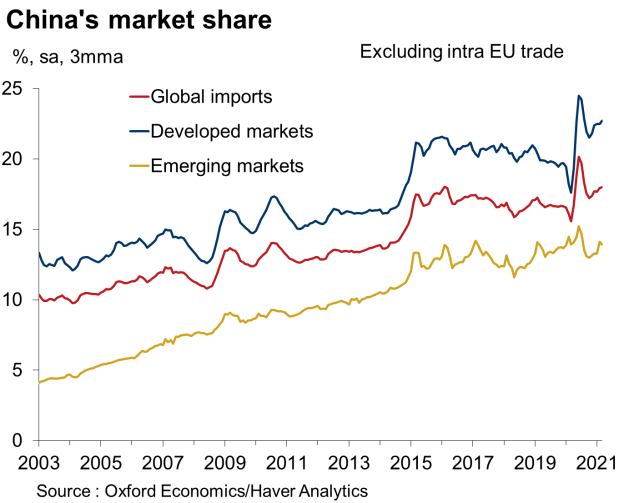

Despite the cry of political leaders that US companies should decouple from China, there’s no evidence that it is happening. The enormous backlog of ships waiting to offload their cargo at ports around the world exemplifies what Oxford Economics’ own data shows: after falling in the first few months of the pandemic, China’s share of global exports has risen dramatically.

Despite the cry of political leaders that US companies should decouple from China, there’s no evidence that it is happening. The enormous backlog of ships waiting to offload their cargo at ports around the world exemplifies what Oxford Economics’ own data shows: after falling in the first few months of the pandemic, China’s share of global exports has risen dramatically.

Moreover, for a recent report commissioned by the Consumer Technology Association, we spoke to US manufacturers of audio equipment and electronics, which are mainly produced in China. We found no evidence that US firms are prepared to retreat from China, or to open factories elsewhere to replace Chinese facilities. “Just not going to happen,” is what one executive told us.

firms are prepared to retreat from China, or to open factories elsewhere to replace Chinese facilities. “Just not going to happen,” is what one executive told us.

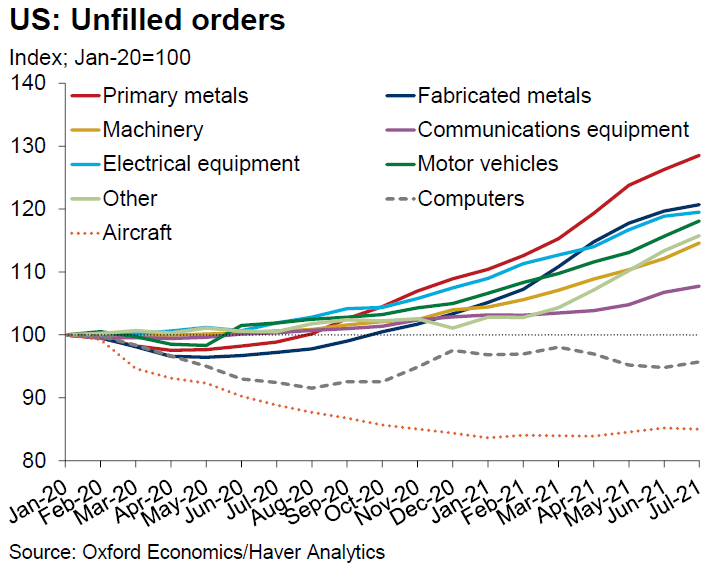

It is remarkable to witness the growing antipathy towards China in the political realm when US dependence on Chinese-produced goods seems as significant as ever. Indeed, the backlogs across supply chains in the United States—from semiconductors to basic materials—only highlight that global interdependence has not diminished nearly two years into the pandemic.

This political and economic contradiction is not only self-defeating, it can damage US interests. It’s hard to imagine America seriously tackling climate change, the North Korean nuclear threat, or other vexing global problems unless the two countries can find common ground.

The Chinese system does face monumental challenges. The Evergrande debacle will test China’s willingness to use state funds to bolster wobbly private firms. Corrupt companies do benefit from government largesse. And foreign companies have been forced to give up intellectual property or ownership stakes to keep doing business in China—a price they are willing to pay for a share of China’s enormous and rapidly growing market.

But China’s party-controlled system also offers certain strategic advantages. The government can champion domestic industries, outline long-term investment goals, and has little problem putting its money where its mouth is. In contrast, the US Congress is still dallying over infrastructure investments both parties know the country desperately needs.

Americans shouldn’t think decoupling from China represents a live option. US Trade representative Katherine Tai made this point recently during a major address unveiling the Biden administration’s trade priorities with China—which, in the end, do not differ markedly from Trump’s.

Asked about decoupling, Ms. Tsai shifted gears: “Maybe the question is whether or not the United States and China need to stop trading with each other. I don’t think that’s a realistic outcome in terms of our global economy. I think that the issue perhaps is, what are the goals we’re looking for in a kind of re-coupling? How can we have a trade relationship with China where we are occupying strong and robust positions within the supply chain and that there is a trade that’s happening, as opposed to a dependency?”

Indeed, America is going to have to learn to compete and cooperate with China, while strengthening its domestic competitiveness and industrial and technology capacity. That’s a contradiction we are all going to have to live with.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

Can Indian manufacturing capitalise on US-China tensions?

India has benefited from US trade rerouting away from China since 2018, albeit to a much lesser extent than some of its Asian peers. India's export strengths largely lie in sectors of the 'old economy', where growth potential is limited and competition is fierce. We estimate that the US-China trade war so far has improved India's export prospects only to a limited extent, dashing hopes that an escalation of the conflict could boost the lagging manufacturing sector.

Find Out More

Post

Business Standard: India’s missed trade opportunities as others gain from US-China tensions

India has not been able to attract a notably greater share of global FDI. Some of this is due to political resistance to stronger ties with China, some of it is held back by structural barriers

Find Out More

Post

Rethinking China’s productivity prospects in the era of AI

Adverse demographic trends imply that the only alternative for sustaining China's longer-term growth momentum would be to sharply accelerate productivity growth. The timely emergence of generative AI could partially close this gap.

Find Out More