Blog | 19 May 2021

Why critics of President Biden’s American Rescue Plan are getting it wrong

With the American Rescue Plan, US President Biden is implementing a stimulus program of historic proportions. Coming on top of the highest debt-to-GDP ratio the US has ever seen, this is raising fears that the government could be spending too much, entailing more negative than positive consequences. Even economists that had, until now, very prominently called for increases in public spending seem to be intimidated by the magnitudes of money now involved (most notably former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers and former IMF Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard).

Fears about this unparalleled spending splurge fall into two classic categories—the negative consequences in the short run, and those of the long term. In the short- to medium run, the economy could be running “too hot,” forcing the Fed to react early and quickly to avoid run-away inflation. This in turn could destabilise asset markets, whose high valuations heavily rely on ultra-low interest rates and continued QE (as we have argued in a previous blog post). In the long-run, the surging debt-to-GDP ratio could become unsustainable once interest rates rise, raising the spectre of a US default.

But what these arguments miss is that the short- and long-run are not independent of each other. This is a fallacy that has permeated economic thought for ages, where generations of economists have been taught that long-run growth and short-run business cycles can be studied independently. According to standard theory, the forces behind long-run growth are determined by the supply side, with engines such as productivity growth, population growth, and education. By contrast, business cycles are mostly driven by demand-side factors. Once a business-cycle shock peters out, the economy supposedly trends back to its long-run growth path.

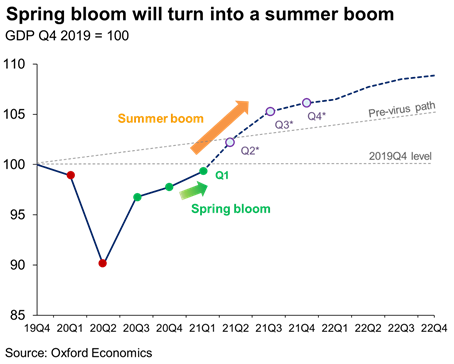

This two-fold structure underlies many modern macroeconomic workhorse models used by central banks and academics alike (one exception being the Oxford Economics Global Economic Model). But it may very well be wrong, and this is where Biden’s stimulus package comes in. As we have argued early on, the American Rescue Plan is likely to run the economy hot, but this is fully intended. Inflation will probably overshoot 2% for several years, but that’s in line with the Fed’s new mandate, with run-away inflation a very remote possibility. So all the traffic lights for activity are on green, flashing a clear signal to companies to go for it: hire and invest all you can, as the next decade is looking great. The government is doing a huge experiment trying to align expectations of the private sector and thereby shape a new long-run equilibrium. The spending plans are meant to simultaneously push the equilibrium rate of unemployment down, push investment up, and raise growth expectations.

Hence, by running the economy hot in the short- to medium-run the US government is increasing long-run growth potential, thereby making the debt-to-GDP ratio sustainable and limiting inflationary pressures. Larry Summers is right in arguing that there are multiple equilibria in the future. But by arguing that overspending may push the economy towards an unsustainable debt-to-GDP ratio he may be understating the amount to which the numerator (GDP) could rise in the long-run, because he employs models that insufficiently account for the impact of demand-side stimulus on long-run potential growth.

If Biden succeeds in his huge macroeconomic experiment—and he well may—this would not only re-establish the US as the leading global player, but also cause a paradigm shift in our economic thinking.

Tags:

You may be interested in

Post

US Key Themes 2026: Exceptionalism amid fragmentation

US exceptionalism is alive and well, and that won't change in 2026.

Find Out More

Post

US Bifurcated ꟷ Economic backdrop deepens racial disparities

Black and Hispanic households have experienced more inflation than other groups since the reopening of the economy from the pandemic lockdowns. Although there've been many phases of high inflation, some have disproportionately hurt these minority groups, such as the jump in energy prices following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, with the ensuing surge in rental inflation further setting them back.

Find Out More

Post

US economic outlook 2026: Four key calls for the year

US exceptionalism will continue in 2026—but so will the vulnerabilities beneath the surface.

Find Out More

Post

US Shipping freight rates on track to stay low in 2026

Our supply chain stress index moderated in September as import volumes continue to decline following front loading activity earlier this year. High frequency data shows that this trend has kept up in Q4, meaning port congestion is unlikely to become a concern.

Find Out More